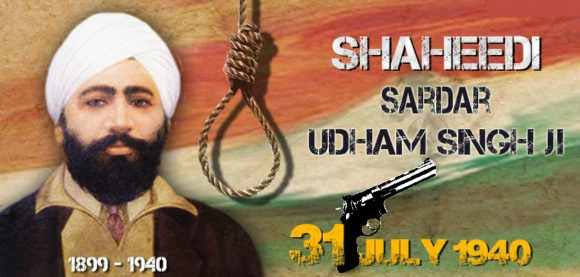

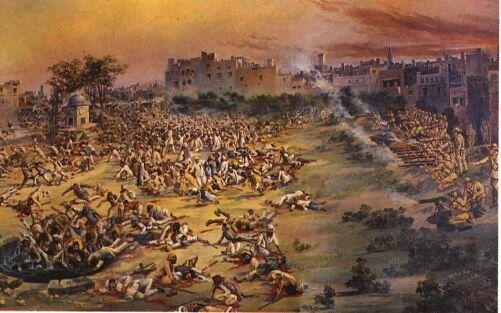

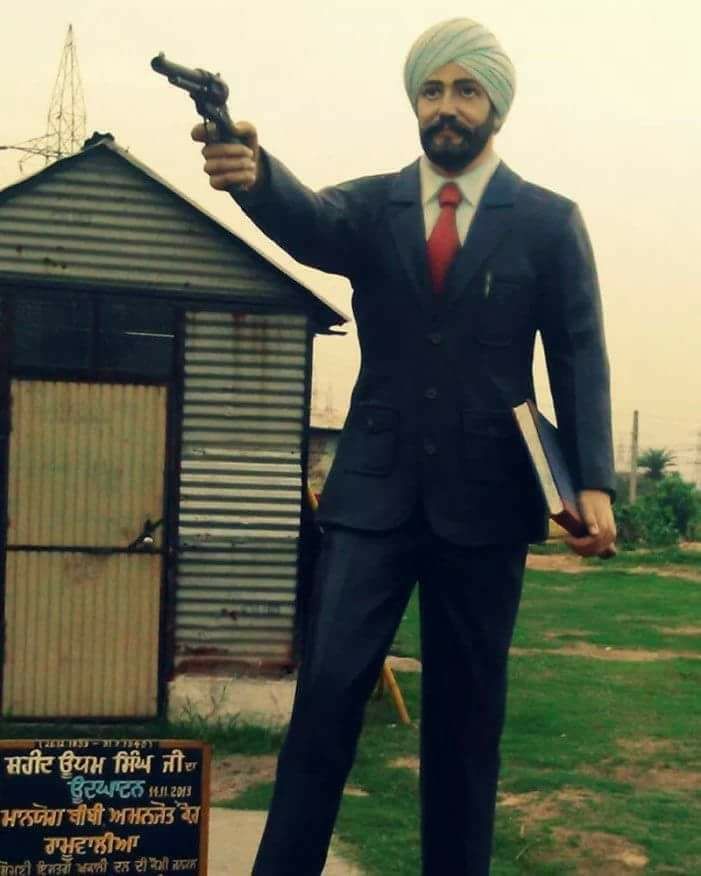

Shaheed Udham Singh (26 December 1899 – 31 July 1940), was a revolutionary belonging to the Ghadar Party best known for his assassination in London of Michael O’Dwyer, the former lieutenant governor of the Punjab in India, on 13 March 1940 . The assassination was in revenge for the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar in 1919 for which O’Dwyer was responsible.Singh was subsequently tried and convicted of murder and hanged in July 1940. While in custody, he used the name Ram Mohammad Singh Azad, which represents the three major religions of Punjab and his anti-colonial sentiment.

Shaheed Sardar Udham Singh is a well-known figure of the Indian independence movement. He is also referred to as Shaheed-i-Azam Sardar Udham Singh (the expression “Shaheed-i-Azam”, means “the great martyr”). A district (Udham Singh Nagar) of Uttarakhand was named after him to pay homage in October 1995 by the then Mayawati government.

important dates

Birthday- 26 Maonal life Imrch 1899

Obit day- 31 July 1940

Important places

Place of birth- Sunam, Punjab (British India)

Obit place- Pentonville Prison (United Kingdom)

Education

Institutions– NA

Educational qualifications- NA

FamilyFather– Sardar Tehal Singh

Mother– NA

Siblings– Mukta Singh

Spouse– NA

Children– NA

Udham Singh was born as Sher Singh on 26 December 1899, at Sunam in the Sangrur district of Punjab, India. His father, Sardar Tehal Singh Jammu, was a railway crossing watchman in the village of Upalli.

After his father’s death, Singh and his elder brother, Mukta Singh, were taken in by the Central Khalsa Orphanage Putlighar in Amritsar. At the orphanage, Singh was administered the Sikh initiatory rites and received the name of Udham Singh. He passed his matriculation examination in 1918 and left the orphanage in 1919.

Shooting in Caxton Hall

On 13 March 1940, Michael O’Dwyer was scheduled to speak at a joint meeting of the East India Association and the Central Asian Society (now Royal Society for Asian Affairs) at Caxton Hall, London. Singh concealed inside his jacket pocket a revolver he had earlier purchased from a soldier in a pub, then entered the hall and found an open seat. As the meeting concluded, Singh shot O’Dwyer twice as he moved towards the speaking platform. One of these bullets passed through O’Dwyer’s heart and right lung, killing him almost instantly. Others injured in the shooting included Sir Louis Dane, Lawrence Dundas, 2nd Marquess of Zetland,[10] and Charles Cochrane-Baillie, 2nd Baron Lamington. Singh was arrested immediately and tried for the killing.

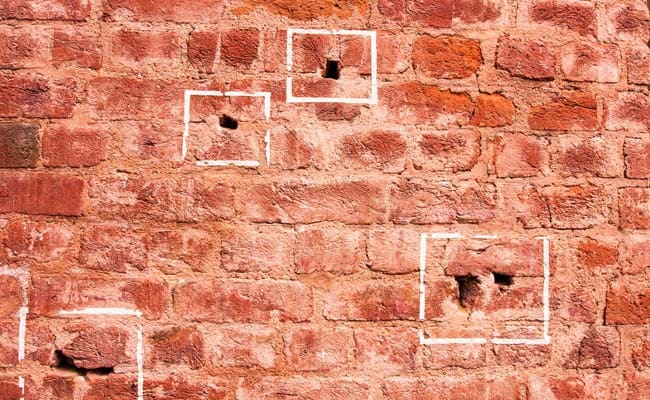

He was present in Jallianwala Bagh onthe day of the massacre (13thApril, 1919) as a helper and was serving water to people present there.

He escaped, but there were deep emotional scars left in his heart that could only heal from revenge.

He dedicated his life to the people of our country and soon after, travelled to the USA where he joined the Ghadar Party in search of more comrades.

He was gathering Indians overseas to fight the colonial rule back home.

He was then called backto India by Bhagat Singh in 1927. He obliged and came back with 25 men and some firearms.

But he was arrested for carrying unlicensed firearms and convicted for 5 years.

During this tenure in prison, General Dyer passed away.On his death bed, he had said:

“So many people who knew the condition of Amritsar say I did right. But so many others say I did wrong. I only want to die and know from my Maker whether I did right or wrong.”

Upon Singh’s release in 1931, under constant surveillance, he somehow made his way to Kashmir and then escaped to Germany where the Nazi regime was growing.

His fellow revolutionaries Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev were hanged that year while he was imprisoned, but he soldiered on.

It was here, in San Francisco, that he first came in contact with the members of the Ghadar Party (a revolutionary movement organised by immigrant Punjabi-Sikhs to secure India’s independence from British rule).

For the next few years, he travelled across America to secure support for their movement, using several aliases such as Ude Singh, Sher Singh and even Frank Brazil.

In 1927, he made his way back to Punjab (on the orders of Bhagat Singh) by working as a carpenter on a ship travelling to India. The same year, he was arrested for the possession of illegal arms and for running the Ghadr Party’s radical publication, Ghadr di Gunj. He was jailed for four years till 1931.

During this period, Brigadier-General Dyer died after suffering a series of strokes while Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev (fellow revolutionaries whom Singh deeply admired) were hanged for their involvement in the Lahore conspiracy case.

Also Read: Legendary Freedom Fighter Bhagat Singh’s Jail Diary Reveals That He Had a Passion for Poetry!

Singh was released in 1931 but remained under constant surveillance of the British police due to his close links with Bhagat Singh’s Hindustan Socialist Republican Association. He made his way to Kashmir, where he used an alias to evade police and escape to Germany.

Singh finally reached England in 1933 with the aim of assassinating Michael O’Dwyer, who he held responsible for the brutal Jallianwala massacre (O’Dwyer had even called the massacre a “correct action”). In London, he fell in with socialist groups while working as a carpenter, motor mechanic and signboard painter.

Udham Singh’s Last Words

On the 31st July, 1940, Udham Singh was hanged at Pentonville jail, London. On the 4th of June in the same year he had been arraigned before Mr. Justice Atkinson at the Central Criminal Court, the Old Bailey. Udham Singh was charged with the murder of Sir Michael O’Dwyer, the former Lieutenant-Governor of the Punjab who had approved of the action of Brigadier-General R.E.H. Dyer at Jallianwala Bagh, Amritsar on April 13, 1919, which had resulted in the massacre of hundreds of men, women and children and left over 1,000 wounded during the course of a peaceful political meeting. The assassination of O’Dwyer took place at the Caxton Hall, Westminster. The trial of Udham Singh lasted for two days, he was found guilty and was given the death sentence. On the 15th July, 1940, the Court of Criminal Appeal heard and dismissed the appeal of Udham Singh against the death sentence.

Prior to passing the sentence Mr. Justice Atkinson asked Udham Singh whether he had anything to say. Replying in the affirmative he began to read from prepared notes. The judge repeatedly interrupted Udham Singh and ordered the press not to report the statement. Both in Britain and India the government made strenuous efforts to ensure that the minimum publicity was given to the trial. Reuters were approached for this purpose.

The father of Udham Singh, Tehl Singh, was born into a poor peasant family and worked as a Railway Gate Keeper at the railway level crossing at Village Uppali. Udham Singh was born on 28th December, 1899 at Sanam, Sangrur District, Punjab. After the death of his father Udham Singh was brought up in a Sikh orphanage in Amritsar. The massacre at Jallianwala Bagh in 1919 was deeply engraved in the mind of the future martyr. At the age of 16 years Udham Singh defied the curfew and was wounded in the course of retrieving the body of the husband of one Rattan Devi in the aftermath of the slaughter. Subsequently Udham Singh travelled abroad in Africa, the United States and Europe. Over the years he met Lala Lajpat Rai, Kishen Singh and Bhagat Singh, whom he considered his guru and ‘his best friend’. In 1927 Udham Singh was arrested in Amritsar under the Arms Act. The impact of the Russian revolution on him is indicated by the fact that amongst the revolutionary tracts found by the raiding party was Rusi Ghaddar Gian Samachar. After serving his sentence and visiting his home town, Udham Singh resumed, his travels abroad. If it was the Jallianwala Bagh massacre which provided the turning point of his life which led him to avenge the dead, it was Bhagat Singh who provided him with the inspiration to pursue the path of revolutionary struggle.

Echoes of Kartar Singh Sarabha and Bhagat Singh may be found in the words of Udham Singh in the wake of the assassination of O’Dwyer.

‘I don’t care, I don’t mind dying. What Is the use of waiting till you get old? This Is no good. You want to die when you are young. That is good, that Is what I am doing’.

After a pause he added:

‘I am dying for my country’.

In a statement given on March 13th, 1940 be said:

‘I just shot to make protest. I have seen people starving In India under British Imperialism. I done it, the pistol went off three or four times. I am not sorry for protesting. It was my duty to do so. Put some more. Just for the sake of my country to protest. I do not mind my sentence. Ten, twenty, or fifty years or to be hanged. I done my duty.’

In a letter from Brixton Prison of 30th March, 1940, Udham Singh refers to Bhagat Singh in the following terms:

‘I never afraid of dying so soon I will be getting married with execution. I am not sorry as I am a soldier of my country it is since 10 years when my friend has left me behind and I am sure after my death I will see him as he is waiting for me it was 23rd and I hope they will hang me on the same date as he was.’

The British courts were able to silence for long the last words of Udham Singh. At last the speech has been released from the British Public Records Office.

Shorthand notes of the Statement made by Udham Singh after the Judge had asked him if he had anything to say as to why sentence should not be passed upon him according to Law.

Facing the Judge, he exclaimed, ‘I say down with British Imperialism. You say India do not have peace. We have only slavery. Generations of so called civilization has brought for us everything filthy and degenerating known to the human race. All you have to do is read your own history. If you have any human decency about you, you should die with shame. The brutality and bloodthirsty way in which the so called intellectuals who call themselves rulers of civilization in the world are of bastard blood…’

MR. JUSTICE ATKINSON: I am not going to listen to a political speech. If you have anything relevant to say about this case say it.

UDHAM SINGH: I have to say this. I wanted to protest.

The accused brandished the sheaf of papers from which he had been reading.

THE JUDGE: Is it in English?

UDHAM SINGH: You can understand what I am reading now.

THE JUDGE: I will understand much more if you give it to me to read.

UDHAM SINGH: I want the jury, I want the whole lot to hear it.

Mr. G.B. McClure (Prosecuting) reminded the Judge that under Section 6 of the Emergency Powers Act he could direct that Udham Singh’s speech be not reported or that it could be heard in camera.

THE JUDGE (to the accused): You may take it that nothing will be published of what you say. You must speak to the point. Now go on.

UDHAM SINGH: I am protesting. This is what I mean. I am quite innocent about that address. The jury were misled about that address. I am going to read this now.

THE JUDGE: Well, go on.

While the accused was perusing the papers, the Judge reminded him ‘You are only to say why sentence should not be passed according to law.’

UDHAM SINGH (shouting): ‘I do not care about sentence of death. It means nothing at all. I do not care about dying or anything. I do not worry about it at all. I am dying for a purpose.’ Thumping the rail of the dock, he exclaimed, ‘We are suffering from the British Empire.’ Udham Singh continued more quietly. ‘I am not afraid to die. I am proud to die, to have to free my native land and I hope that when I am gone, I hope that in my place will come thousands of my countrymen to drive you dirty dogs out; to free my country.’

‘I am standing before an English jury. I am in an English court. You people go to India and when you come back you are given a prize and put in the House of Commons. We come to England and we are sentenced to death.’

‘I never meant anything; but I will take it. I do not care anything about it, but when you dirty dogs come to India there comes a time when you will be cleaned out of India. All your British Imperialism will be smashed.’

‘Machine guns on the streets of India mow down thousands of poor women and children wherever your so-called flag of democracy and Christianity flies.’

‘Your conduct, your conduct – I am talking about the British government. I have nothing against the English people at all. I have more English friends living in England than I have in India. I have great sympathy with the workers of England. I am against the Imperialist Government.’

‘You people are suffering – workers. Everyone are suffering through these dirty dogs; these mad beasts. India is only slavery. Killing, mutilating and destroying – British Imperialism. People do not read about it in the papers. We know what is going on in India.’

MR. JUSTICE ATKINSON: I am not going to hear any more.

UDHAM SINGH: You do not want to listen to any more because you are tired of my speech, eh? I have a lot to say yet.

THE JUDGE: I am not going to hear any more of that statement.

UDHAM SINGH: You ask me what I have to say. I am saying it. Because you people are dirty. You do not want to hear from us what you are doing in India.

Thrusting his glasses back into his pocket, Udham Singh exclaimed three words in Hindustani and then shouted, Down with British Imperialism! Down with British dirty dogs!’

As he turned to leave the dock, the accused spat across the solicitor’s table.

After Singh had left the dock, the Judge turned to the Press and said:

‘I give a direction to the Press not to report any of the statement made by the accused in the dock. You understand, members of the press?’

Lalkar, July-August, 1996.